"I think we are drawn to dogs because they are the uninhibited creatures we might be if we weren't certain we knew better. They fight for honor at the first challenge, make love with no moral restraint, and they do not for all their marvelous instincts appear to know about death. Being such wonderfully uncomplicated beings, they need us to do their worrying."

Troubles With Bird Dogs and

What to Do About Them (1975)by George Bird Evans

The day after Benji's tragic and untimely end, Cheryl visited the local animal shelter where we rescued him in search of some solace. Was it too soon? Probably, but there is no salve for loss as soothing as the replacement of the very thing we lost. That is not to say that Benji is so easily replaceable, but we had so much love for him that it would be a shameful waste to direct every ounce of it to grief. Instead we sought to give that love to another creature which deserves it, if only because it is still alive.

On 23rd of August, exactly three days after Benji's passing, we brought a new puppy home.

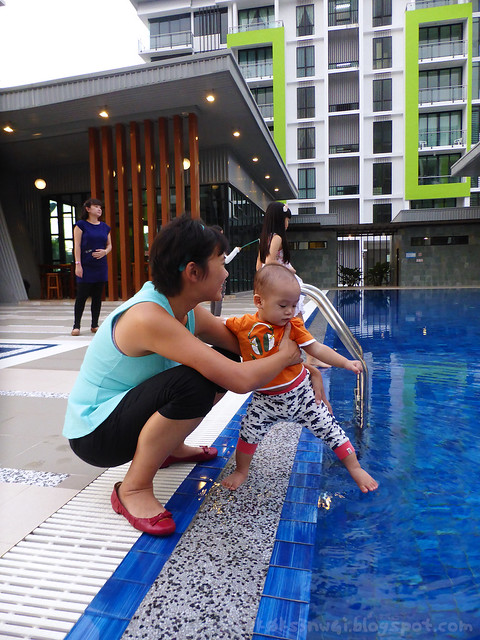

|

| At the shelter. |

On the way back, Cheryl christened her Zoë, apropos of nothing. When I looked it up later, I found that it is Greek and it means "life" or "alive", which is thought is delightful serendipity. There is nothing more antithetical to the deathly, funereal pall that have settled over our family than bounding, barking, warm, furry life. We needed this. I needed this.

|

| Zoë, in her crate, in the middle of crate training. |

Zoë was very different from Benji, both in personality and temperament. To get the most obvious things out of the way first, she was female and was only about 2 months old (compared to 4 months old male Benji). While Benji was calm, confident and deliberate, Zoë was a firecracker - a wilful, hyperactive little bitch. The only time Benji got really excited was when he saw the cats, which he would chase in delight. Zoë however, have never shown any sign of noticing her feline housemates' existence at all. House training her was a more strenuous affair because of her weak puppy bladder so I was forced to wake up every 2 hours at night to let her water (or fertilise) the garden.

While Benji happily accepted his usual mealtime kibbles as training treats, Zoë proved to be a fussy, picky customer. She wouldn't even touch her dry puppy kibbles unless I mix it up with a spoonful of meaty wet food first. And since training treats have to be equal to or more "valuable" than her usual feed, I was forced to train her only at mealtimes, giving her spoonfuls of her food for each time she complied with commands. Eventually, I resorted to baking chicken liver for this purpose and thankfully, she deemed it a worthy enough payment in exchange for tricks.

|

| Sophie, already plotting Zoë's downfall from day one. |

Fortunately, with a bit of persistence, she was house trained and became "accident-free" within 3 days and could even hold it in through the night. Within a week, she learned to sit and lie down on command. She could even stand on her two hind legs for 1 to 2 seconds when asked, a trick I could never get Benji interested in.

Last Friday, a day before my son's one year old birthday, Zoë died. If this came as a rude surprise as you are reading this, it's because it was for us too.

|

| Pretty girl. |

On Thursday, 4th of September, Cheryl went to take her out for her evening toilet visit but noticed that there was something very wrong with her. I saw that she was holed up inside her crate and stood up, wagging her tail when I approached. However, I noted that she was not leaving her little sanctuary like she usually did. I peered inside and noticed that she was leaning on her left, her left wrist slack and floppy.

I reached in for her but she freaked out and scrabbled backwards, something she had never done. She had a sweet, outgoing and confident disposition, and had never displayed any neuroses prior to this. I carried her out gingerly and placed her on the floor to get a better look at her - and she immediately panicked and began running in circles, persistently falling to her left. She was also drooling like a faucet. I studied human medicine, but what Zoë exhibited were unmistakably neurological symptoms. But why? Cheryl just took her out a few hours prior but she was perfectly fine! The only thing that happened that day to her was her 2nd ivermectin jab, which she was on because she brought mange home with her from the shelter which had left her mostly bald with lots of sores from scratching (quite unlike her pictures here), but was otherwise completely well and active. We fully expected her to recover from it.

We rushed her to a nearby vet who found that her pupils were also dilated and she was exhibiting what he called "knuckling" where Zoë's doesn't notice when her paws were placed in odd, uncomfortable positions - indicating a loss of proprioception. He diagnosed her with ivermectin toxicity, gave her a shot of corticosteroids and a bolus of subcutaneous fluid between her shoulders because she was not eating or drinking. The vet also gave me a syringe loaded with diazepam, in case she started fitting that night. And that night, I learned practically everything there is to know about ivermectin sensitivity in dogs, how it afflicts certain dog breeds that happen to carry the MDR-1 gene defect which impairs a dog's ability to transport certain compounds out of their brains, leading to a build up. I slept in the living room as well so I could hear it if Zoë starts fitting. I fed her some of her favourite wet dog food from a can using a spoon, and was heartened to see that she could still lick it up and swallow. Her tail still wagging like a windmill, which I understand doesn't necessarily meant that she was happy. When I carried her down to the garden to pee, she could still do her half-crouch.

We brought her back to the vet the next morning as advised but found that Zoë's condition worsened. She had started making chewing movements with her mouth. The vet look at that odd behaviour thoughtfully and then swabbed some of the tears streaming out of her eyes, pipetting some of it onto a plastic cartridge that resembles a urine pregnancy test. He showed it to me and told me that it was an antigen test for canine distemper. One very bold line showed on it.

"One line," I said. "That's good news right?"

"That is the 'test' line you are seeing. The 'control' line have yet to appear, but you can see it forming faintly now," he said sadly.

Oh no...

Now all my confusion made sense. Why Zoë did not react to the first ivermectin shot, why she was suddenly struck with very severe generalised mange - which indicated that her immune system was failing. "But she already received her 1st shot of vaccination!" I told the vet but I knew the answer before he even answered. She had contracted it at the shelter before she was vaccinated, and the virus must have been incubating till now.

I am a doctor myself and I knew that we were at a crossroads of hard decisions. "When should we give up?" I asked calmly.

"When she fits non-stop," he told me. "Or when she is completely unable to eat or drink."

By noon, Zoë was a shambles of her former self; blind, highly nervous and likely delirious. Her jaws have started locking up and it was difficult for me to pry them apart and syringe some food into her mouth. Cheryl received word from the shelter that Zoë's litter mates have also started displaying signs of distemper two days ago, which pretty much proved that Zoë was exposed to the canine distemper virus before we took her home. She was a time bomb ticking to heartbreak, but we were completely unaware. I did more reading (as I am wont to do in times of crises) but the more I read, the more hopeless it seemed, and Zoë, at this point, had deteriorated to a state where she couldn't even crouch to urinate. It just dribbled out as she stood there seemingly oblivious to her own bladder movement. Finally, Cheryl and I decided on what we felt was right: we decided to put Zoë to sleep.

We took her back to the vet, who seemed to have been expecting us. This time, we were directed to a different room and in the middle of it was a large stainless steel table. We were asked to sign some papers and after we gave Zoë her last pets, the vet gave her a lethal dose of pentobarbitone - and just like a robot powering down, she slumped down gently onto the table surface, her head flopped to one side unnaturally. The room filled with the smell of faeces as whatever that remained in Zoë's rectum oozed out. Cheryl cried. I was too numb to follow suit. After a minute, the vet checked her for any signs of life and finding none, asked us if we would like him to dispose of her for us.

"No thanks," I said. "We are taking Zoë home with us."

The orderly there offered us a plastic bag - and we refused because it just didn't seem right. I put her back in her crate and drove her back to our house. There, I dug her a grave beside Benji's, and after wrapping her in the blanket she always slept on, buried her with her bright blue collar. I comforted myself with the thought that at least Zoë did not suffer long and had spent her last hours with people who loved her most instead of a cold, harsh metal cage at the animal shelter. In the last two weeks, she ate better than she ever had in her life and had toys (and feet) to chew. Her weight almost doubled under our care. We did everything right by her and told ourselves was not our fault she was already doomed from the get go.

But it was still painful as hell.

Zoë's human,

k0k s3n w4i